I’ll be honest, I don’t know as much about railway and trains as I would like. It was dad who was the steam buff; he would write and narrate the scripts, and I would do the filming and editing. We made a great team.

The blog that I have stared on this site, has been about the closed stations on some of the video dad and I made. However, I like to think that ‘everyday is a school day’, so I wanted to teach myself more about the railways.

My first foray into this is learning more about the closure of the railways and who, or what, caused it.

Who Closed all the railway stations?

That is a question that still echoes through British communities decades later, especially in rural areas where the loss of a local station severed vital connections.

The short, popular answer points to Dr Richard Beeching, the physicist-turned-railway-boss whose name became synonymous with destruction. However, the reality is far more complex—and politically charged—than one man wielding an axe.

In the early 1960s, Britain’s nationalised railway system was haemorrhaging money. British Railways was losing around £140 million annually amid rising car ownership, expanding motorways, and competition from buses and lorries. The network, built in the Victorian era for a horse-and-cart world, had become bloated with lightly used branch lines and small stations. Something had to give. Dad would make little jokes about accountants closing the railways, he did this because he was an accountant.

Enter Dr Beeching

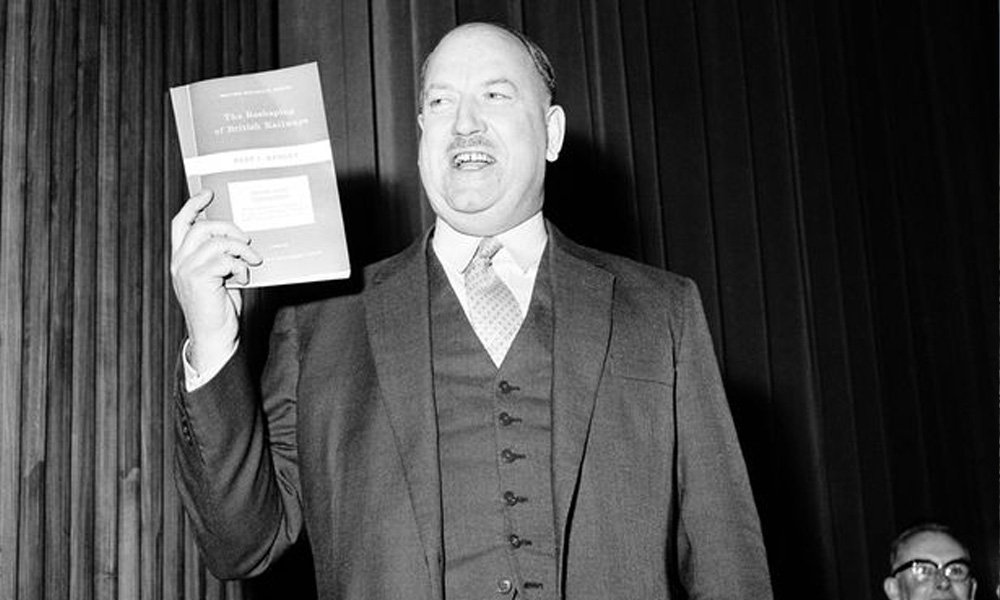

Dr Richard Beeching was appointed in 1961 as chairman of the British Railways Board by Conservative Transport Minister Ernest Marples, Beeching was tasked with making the railways pay—or at least stop bleeding public funds. His 1963 report, The Reshaping of British Railways (often called Beeching I), was blunt: close around 2,363 stations, axe 5,000 miles of track (about 30% of the network), and eliminate thousands of loss-making services. A follow-up report in 1965 focused investment on core trunk routes.

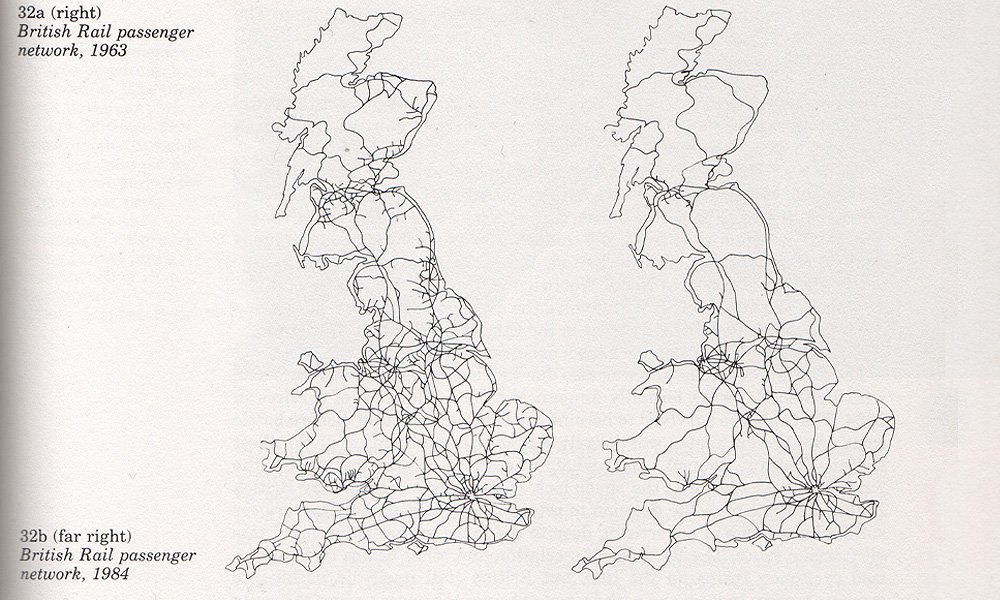

The closures that followed—peaking in the mid-1960s—became known as the Beeching cuts or Beeching Axe. Over 2,000 stations vanished, along with branch lines serving remote villages, market towns, and holiday spots. Iconic routes like the Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway and sections of the Great Central Main Line disappeared entirely. Communities protested, MPs lobbied, and some lines were saved—but most fell.

Was it all Dr Beeching?

Yet Beeching didn’t personally close a single station. He produced recommendations based on traffic data and financial analysis. The actual decisions rested with politicians. The Conservative government under Harold Macmillan and Alec Douglas-Home welcomed the report. When Labour won power in 1964 under Harold Wilson, many expected reversal—Labour’s manifesto had criticised “major closures.”

Instead, Transport Minister Barbara Castle and her successors pressed ahead with most of Beeching’s programme, implementing the bulk of closures between 1964 and the early 1970s. Some argue Labour went further in certain cases, prioritising deficit reduction over rural connectivity.

Beeching resigned in 1965, his job largely done, and later received a peerage. He became the scapegoat: the cold, detached technocrat who “destroyed” the railways. In truth, the closures reflected broader societal shifts—cars were king, roads were prioritised, and subsidies were politically toxic. Many lines were genuinely unviable by then, carrying handfuls of passengers.

If they were still in use today

Today, hindsight is kinder to some lost routes. Rising rail patronage, environmental concerns, and campaigns have reopened a few lines (the Borders Railway in Scotland, for example), but most remain footpaths, cycleways, or lost forever. I’ve been recently covering the Plymouth to Launceston railway, and you can still walk or cycle a lot of it today.

The question isn’t really “who closed all the stations?”—it’s why Britain allowed such drastic pruning of a once-dense network.

Beeching’s report was the catalyst, but governments of both colours swung the axe. The real culprits? A changing world, short-term financial thinking, and a failure to foresee rail’s renaissance.

Up Next

I hope that’s been as interesting to read as it was to write. As I said, I’m covering the Plymouth to Launceston via Tavistock South railway, and the next station on the line was Horrabridge.