In a previous blog post, I asked Who Closed the Railways? Carrying on with my investigation about the closure of the branch lines around the country, I’m asking another question: What lines escaped the Beeching Cuts?

The Beeching Axe

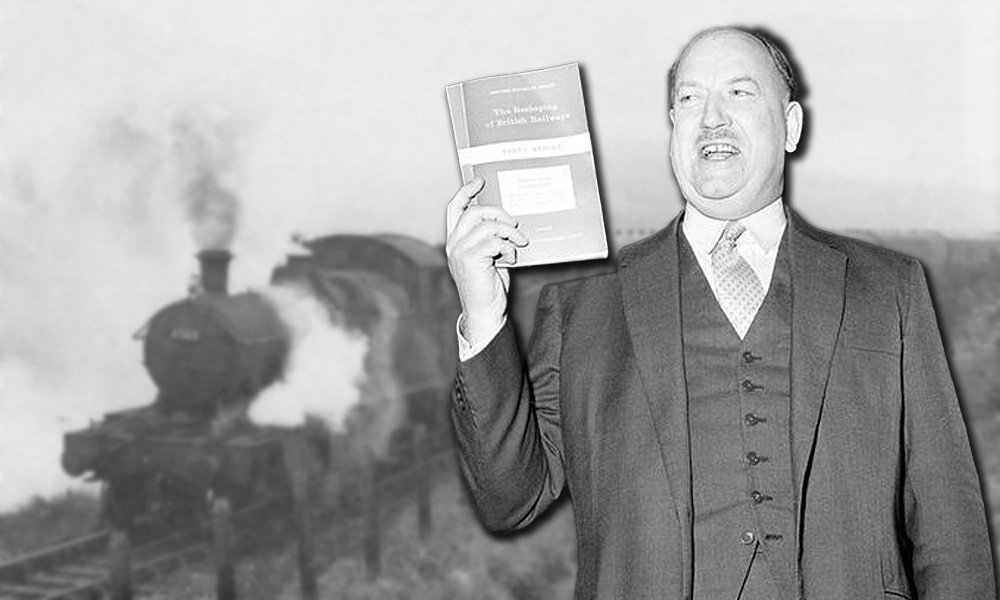

The Beeching cuts, often called the Beeching Axe, represent one of the most dramatic restructurings in British railway history. In 1963, Dr. Richard Beeching, chairman of the British Railways Board, published The Reshaping of British Railways, a report aimed at addressing mounting financial losses amid competition from cars, buses, and lorries. The report recommended closing around 5,000 miles of railway lines, about 30% of the network, and shutting 2,363 stations, representing over half of Britain’s passenger stations. This would eliminate thousands of jobs and affect countless communities across the UK.

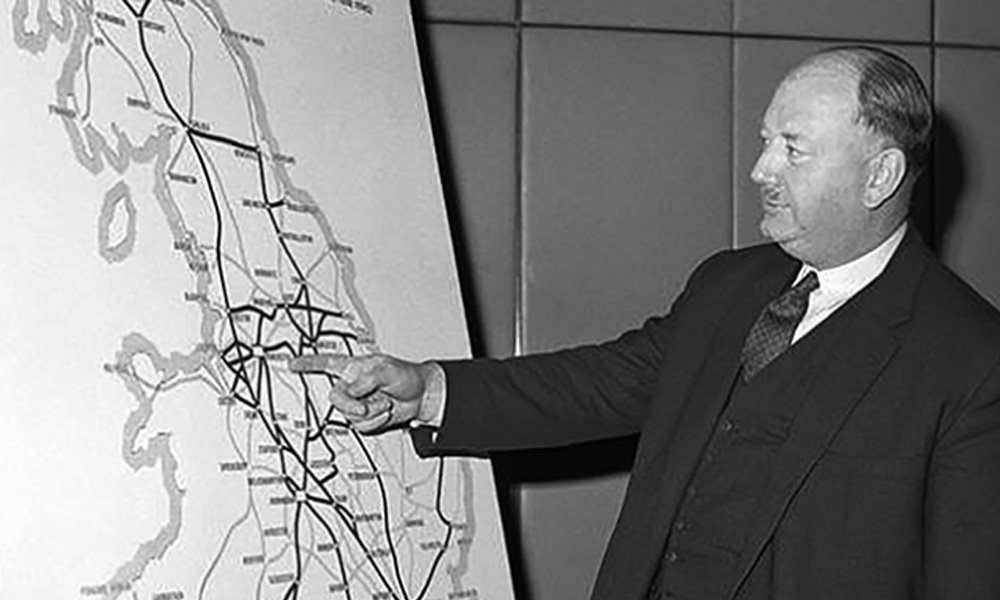

While many recommendations were implemented, leading to over 7,000 miles closed by the early 1970s, several lines were reprieved. Reprieves often resulted from local campaigns, Transport Users Consultative Committee (TUCC) findings on social hardship, political sensitivities (such as marginal constituencies), lack of viable road alternatives, freight importance, tourism potential, or strategic value. Transport Minister Ernest Marples personally reviewed some cases in 1964, sparing certain routes despite Beeching’s proposals.

One of the most celebrated survivors is the Heart of Wales Line (formerly the Central Wales Line, see my video on this line). It ran from Craven Arms to Llanelli through remote mid-Wales. Beeching recommended full closure, but the Ministry of Transport refused. This was partly because the line carried freight to steelworks at Bynea and industrial sites around Ammanford and Pontarddulais, linking them to Llanelli docks.

It also traversed six marginal parliamentary constituencies, making closure politically risky. Reduced to single track for cost savings and later designated a Light Railway in 1972 to simplify operations, the line faced another threat after the 1987 Glanrhyd Bridge collapse, which killed four people in a flooding accident. Unlike the similar Carmarthen-Aberystwyth line (closed after flooding in 1965), cross-party support ensured repairs and survival. Today, this scenic route remains a vital community lifeline and tourist attraction.

Settle to Carlisle Line

Perhaps the most famous escapee is the Settle to Carlisle Line, a stunning 73-mile route across the Pennines. Beeching viewed it as duplicative of the West Coast Main Line and recommended passenger withdrawal. Intermediate stations closed in the 1960s and 1970s, services dwindled to a handful daily. Then, by the 1980s British Rail sought full closure, citing costly repairs to structures like Ribblehead Viaduct.

A massive campaign by the Friends of the Settle–Carlisle Line, local authorities, and enthusiasts highlighted its tourism value, potential as a diversionary route, and growing traffic. Public exposure of inflated repair estimates and “closure by stealth” tactics led to a surge in ridership—from 93,000 journeys in 1983 to 450,000 by 1989. In April 1989, Transport Secretary Paul Channon refused closure consent, repairs proceeded, freight revived, and eight stations reopened.

The line now carries over a million passengers annually and stands as a symbol of successful rail preservation. In Scotland, remote Highland lines also survived due to strong lobbying and social necessity. The Far North Line (Inverness to Wick and Thurso) and Kyle of Lochalsh Line (Inverness to Kyle of Lochalsh) were reprieved in 1964. This was after the Highland lobby argued no realistic road alternatives existed, avoiding widespread hardship for modest savings. These routes served isolated communities and tourism to Skye and the north coast.

Other Lines

Other notable survivors include the Tamar Valley Line (Gunnislake to Plymouth – see my video of this line, From the Cab), preserved due to poor local roads. The Hope Valley Line in Derbyshire; the Marshlink Line (Ashford–Hastings). The Conwy Valley Line; and commuter routes like parts of Merseyside and West Yorkshire networks.

These escapes highlight the limits of Beeching’s purely economic approach. While many lines succumbed to the axe, the survivors, often scenic, socially vital, or politically protected. This demonstrate how community action, strategic importance, and evolving transport needs could prevail. Today, amid railway reopening’s and debates on regional connectivity, these lines underscore the enduring value of Britain’s retained network.

I will be delving more into this subject as time goes on, but in the meantime, I will be carrying on with the posts about the station on the Plymouth to Launceston branch line.